Oct 16 - Oct 30 · Week Five · Studio Practices

The UX of Whispering

Revati Banerji I MA UX Design I London College of Communication

Brief: Design an experience that amplifies the qualities/customs of whispering

Team: Mary Mehtarizadeh · Andre Oliveira Dinis · Yin Hong Clara Chow · Eniola Aminu · Veronika Rovniahina

We began with a simple game of telephone. This exercise, helped confirm several behaviours associated with the act of whispering. People naturally lean in, become aware of breath and proximity, and focus more when listening. Whispering feels intimate. Many participants covered their mouths or cupped their ears, when exchanging a whisper.

Research

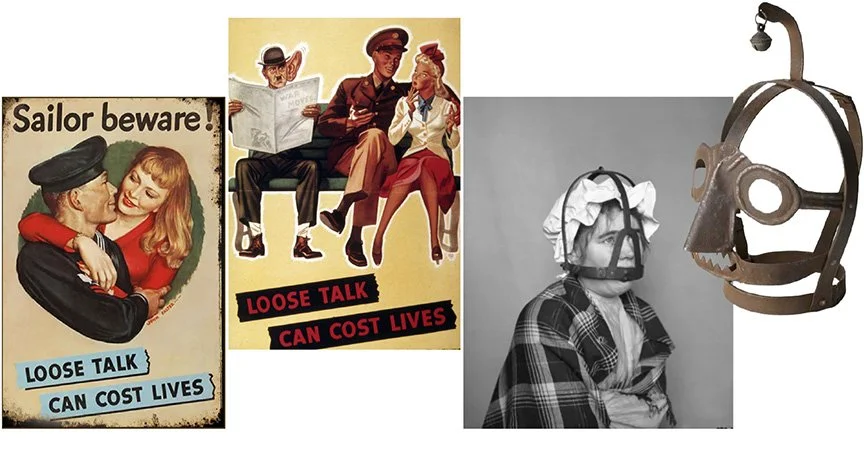

Our secondary research revealed how whispering is deeply gendered. Historically, women have been punished for gossiping, i.e the Scold’s Bridle, a metal cage used as punishment for “gossiping” women. During World War II, the “Loose Lips Sink Ships” campaign warned officials that women’s gossip was dangerous and could reveal military secrets.

Fig. 3. The “loose lips” campaign and the scold’s bridle, a metal cage used to punish talkative women.

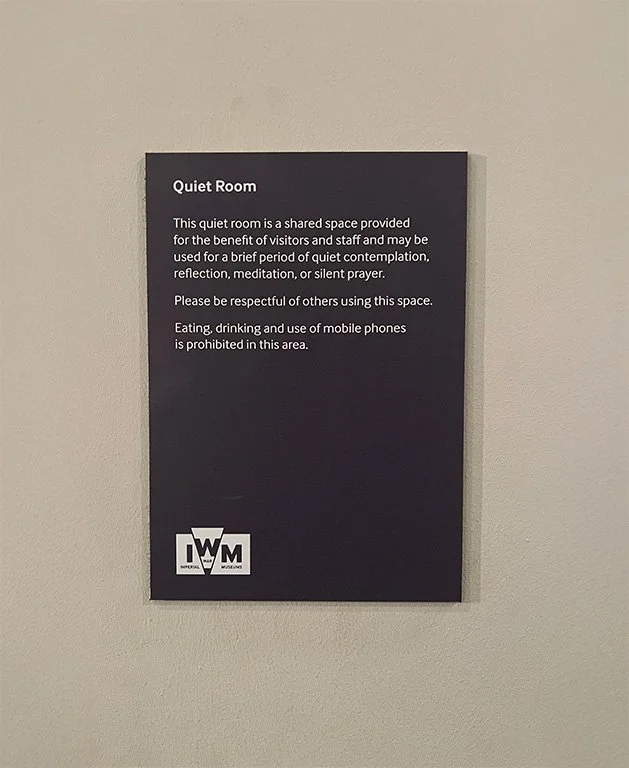

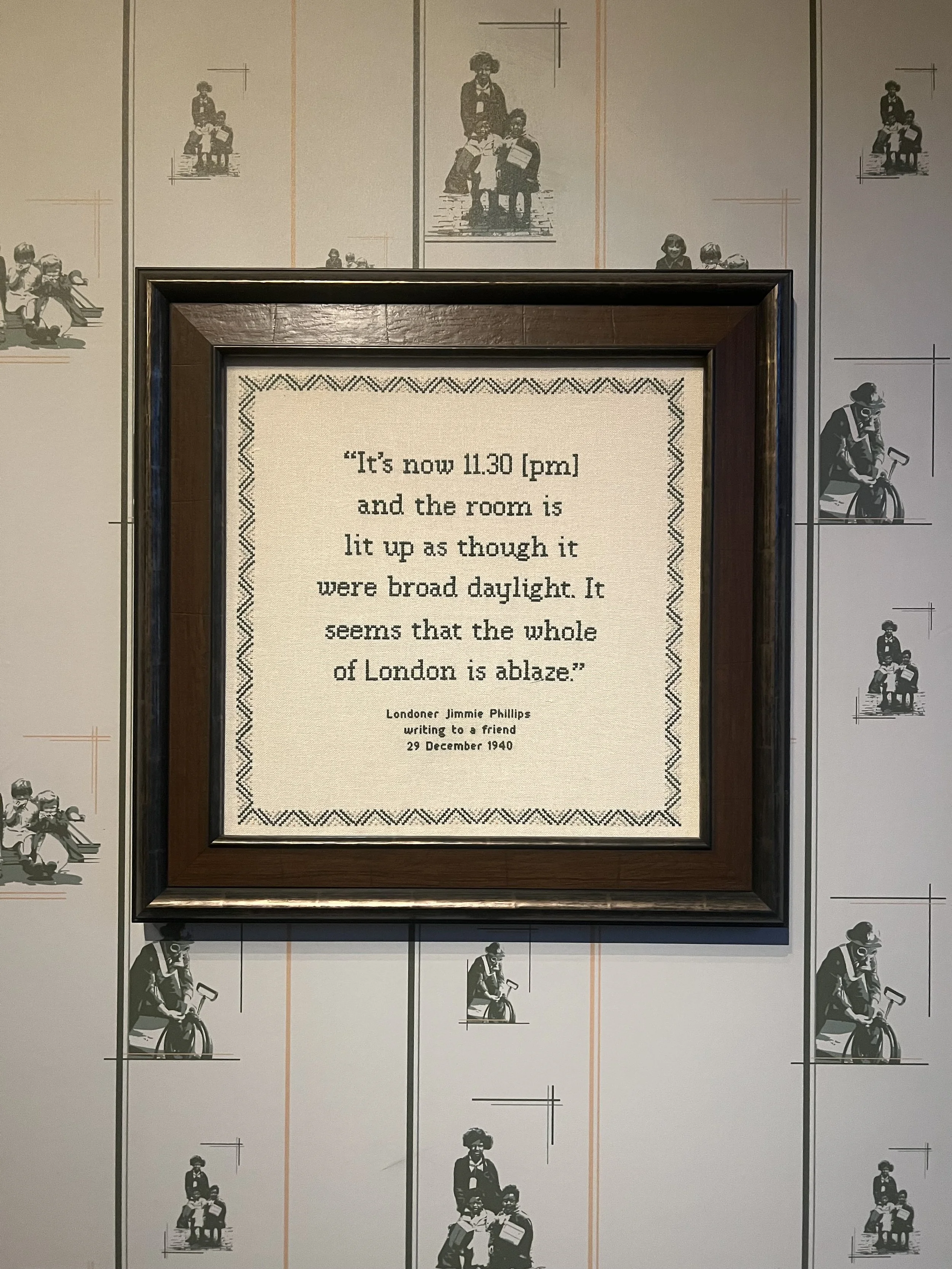

To better understand how space commands whispering and explore the theme of conformity, we visited the Imperial War Museum. While the entrance was busy, loud, and social, sound levels dropped as we moved deeper into the museum. The atmosphere, spatial layout and behaviour of others reinforced whispering.

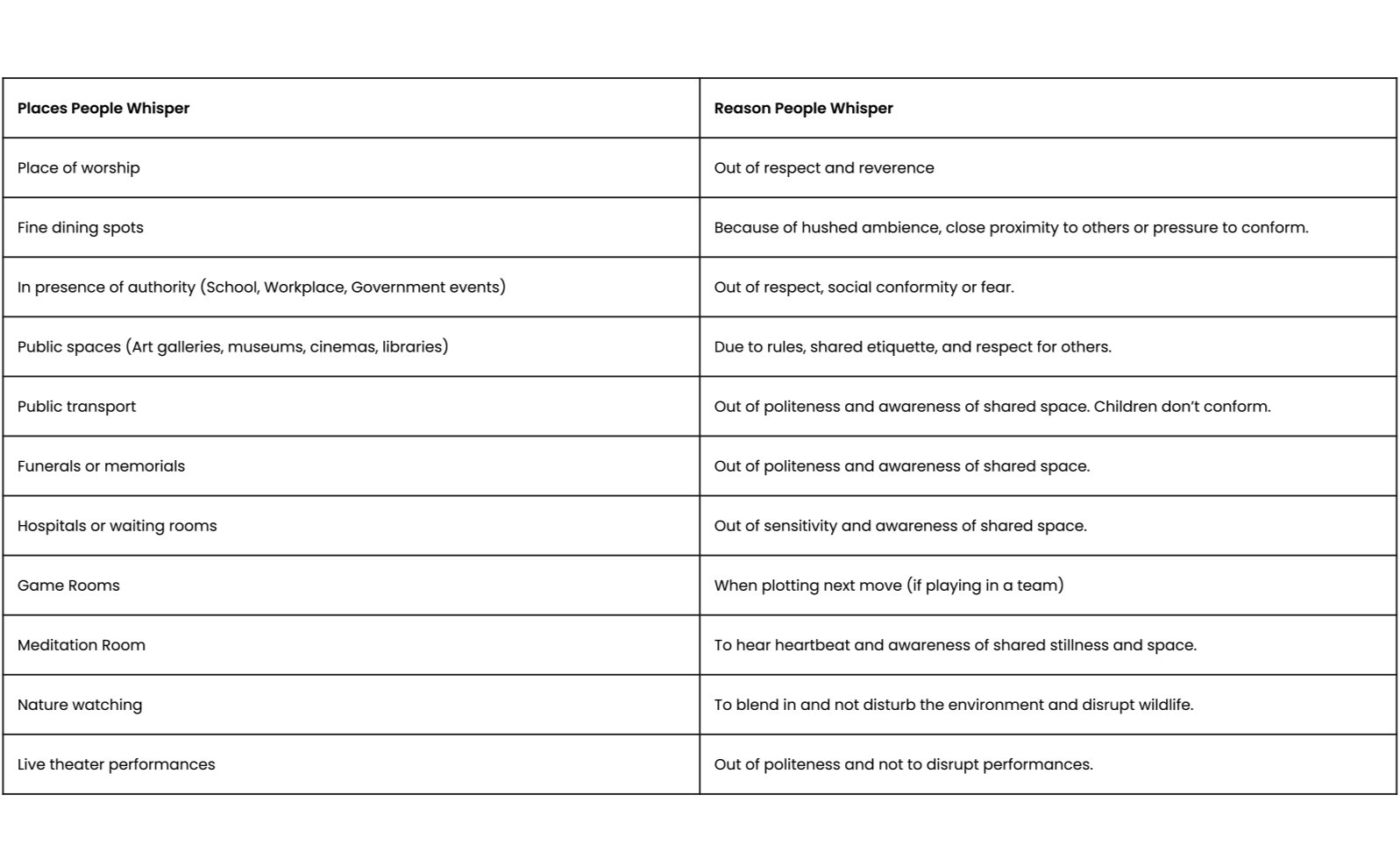

We then began identifying recurring contexts in which people tend to whisper, along with the reasons behind it.

Fig. 2. Initial discussions about where and why people whisper.

Fig. 1. All groups participated in a game of Telephone as part of the inital research. Photography Merrin O’Connor.

Bodystorming

We practised body storming in the museum’s Quiet Room. Speaking aloud felt uncomfortable and unnatural. This reminded me of the onion soup example from our reading, where the author describes feeling uneasy eating insects, because his cultural upbringing made the act feel wrong and his body had a visceral reaction to it. Similarly, the quiet room shaped our behaviour, making talking loudly feel unnatural in a room designed for silence and reflection.

Fig. 5. Bodystorming in a room meant for quiet. Photography by author.

Fig. 4. Trip to the Imperial war museum to observe conformity as a theme for whispering. Photography by author.

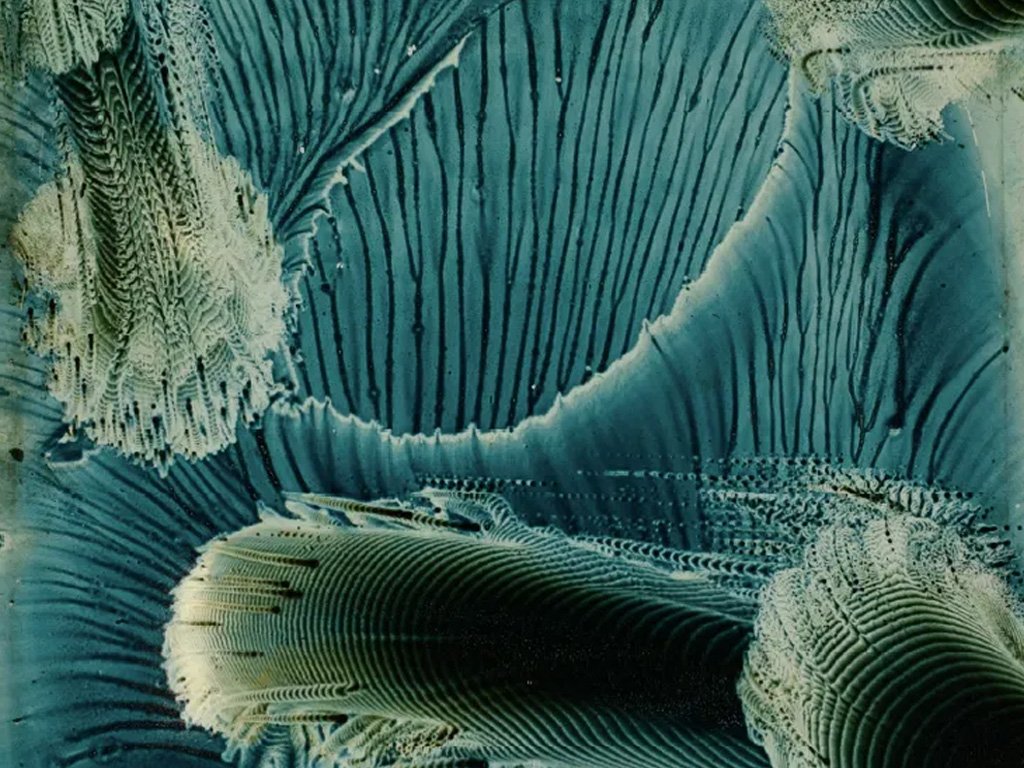

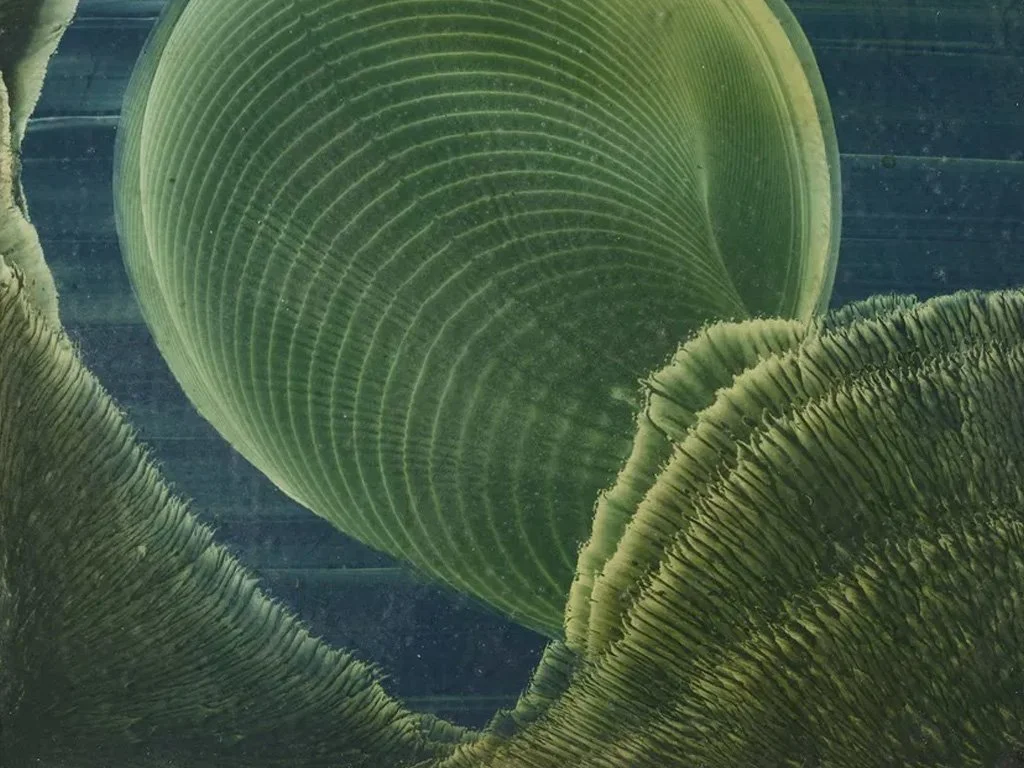

We discovered Margaret Watts Hughes’ Eidophone (1885), where vocal vibrations created patterns in sand on a stretched membrane, highlighting the physical impact of sound.

Fig. 6. Margaret Watts Hughes’ Eidophone (1885). Photography by Louis Porter.

Material

Experimentation

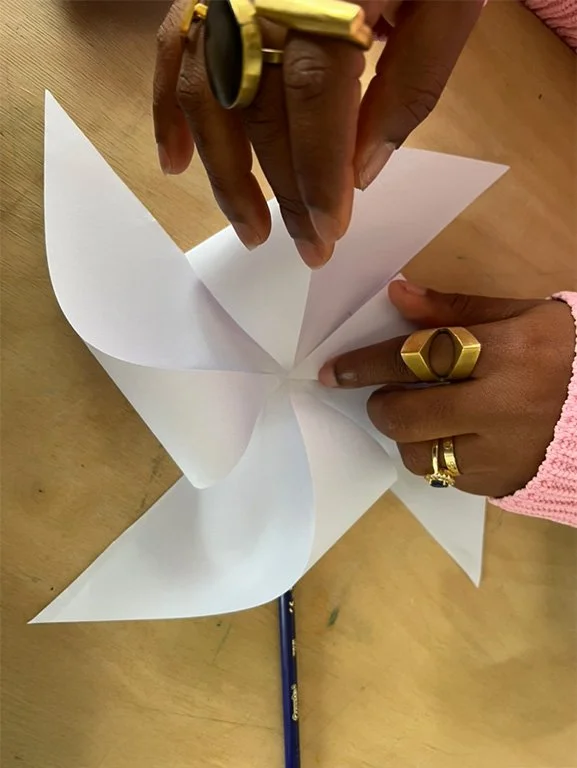

We then shifted our focus to material exploration. We experimented with whispering through tubes, gradually increasing their length, which seemed to make whispers clearer. Inspired by (Fig. 6.) , we attempted whispering into sand through a paper funnel, though this did not produce visible cymatics. Whispering into a bowl of water caused visible ripples, while speaking aloud had no impact on the surface and whispering onto a paper fan did not cause any significant movement.

Fig. 7. Material exploration examining the physical impact of whispering and how materials can enhance it. Photography by author and Veronika Rovniahina.

During our tutorial, we presented our findings. Feedback encouraged us to continue exploring the materiality of whispering rather than its social themes. This week was research and experimentation heavy, even though a clear research question had not yet formed.

References:

Public Domain Review (2023) Picturing a voice: Margaret Watts Hughes and the Eidophone. Available at: https://publicdomainreview.org/essay/picturing-a-voice-margaret-watts-hughes-and-the-eidophone (Accessed: 15 January 2026).

Just, P. and Monaghan, J. (2000) Cultural and Social Anthropology: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.